Perspectives from a student, performer, teacher and composer

The seminar entitled “Globalization and Indian Music,” which took place in Mumbai in January 2002, under the auspices of the Sangeet Research Academy, provided a forum for musicians, teachers, members of the music industry and representatives from government agencies to discuss the significant impact that Indian music has had around the world.

During the discussions there appeared to be some ambiguity as to the actual meaning of the word ‘globalization’, especially since one of its common uses today is associated with western economic expansion throughout the world at the expense of local economies and cultures. As a result, this article will use the phrase ‘global impact’ to describe the effect of Indian music on the lives and interests of music lovers around the world.

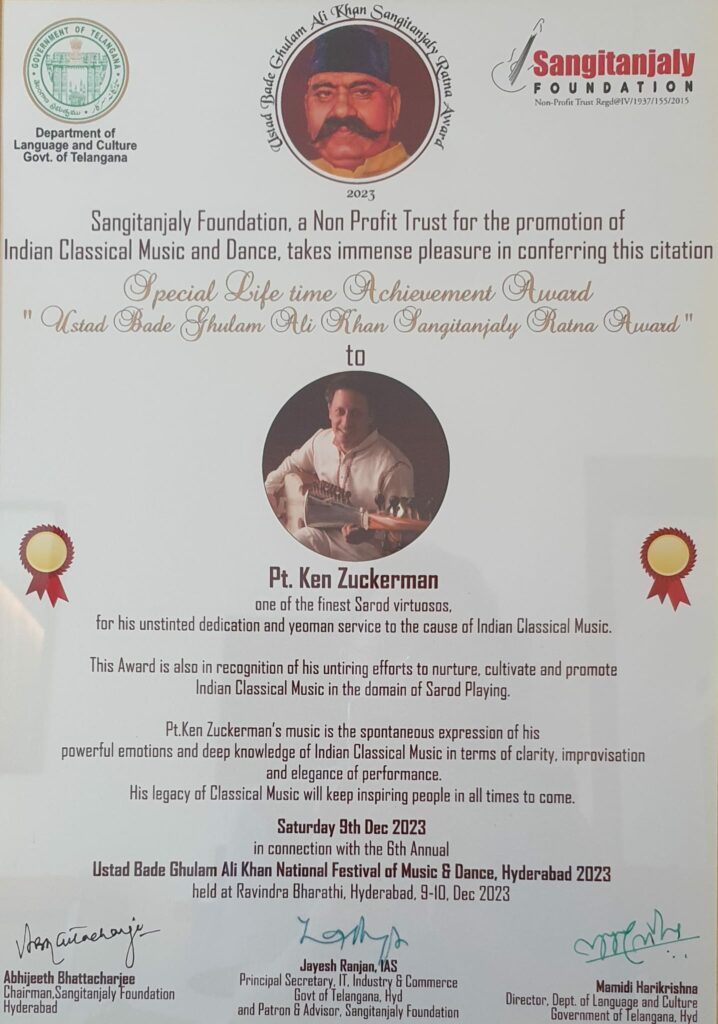

On this subject there is no ambiguity: Indian music has indeed had an extensive impact on music lovers all over the world. Having myself been deeply affected by this impact, I wish to describe the events and experiences during the last thirty years that have helped shape my musical life and career. By citing examples of my own experiences as a student, performer, teacher and composer, I hope to draw attention to several aspects of the global impact of Indian music.

There are four general areas on how this global impact affected my musical development:

I) As a curious music student in search of a style, who meets a master of an ancient musical tradition.

II) As a western performer of Indian music – both in and outside of India.

III) As a music teacher, integrating Indian music pedagogy into the western music classroom.

IV) As a composer exploring the contacts and contrasts between Indian, western, and other music traditions of the world.

I) A curious music student in search of a style meets a master of an ancient musical tradition.

I was fortunate enough to grow up in a place and time, as well as in a family, that encouraged me to follow my curiosity and musical instincts in listening to and experimenting with a wide variety of styles. From pop and rock’n’roll, to jazz, folk, classical and early music, I was able to get a taste of many styles. These I explored both vocally as well as on instruments: piano, guitar, cello and lute. I also happened to be at the right place at the right time, in the late 60’s and 70’s, during the great heyday of Indian music’s popularity in the West. And in 1971, I was fortunate enough to meet the renowned performer and teacher, Ustad Ali Akbar Khan.

Although at the time it seemed to be an accidental meeting, it had been well prepared from many sides. Maestro Khan’s visit to the small college I was attending was a direct result of the great wave of interest in Indian music, partly triggered by George Harrison’s groundbreaking experimentation with the sitar. At that time, my own musical curiosity was also in high gear, and I was ready to try out anything new. After his concert, Ali Akbar Khan announced to his enthusiastic audience that he had recently opened a college in California where any interested student could come and study Indian Music. I remember thinking that this was a rather far-fetched proposition, but as luck or fate had it, the following summer I found myself at the Ali Akbar College, beginning a study of Indian music on the sitar. Before long, the captivating sound of the maestro convinced me to switch to the sarod.

Although there were many new and exotic aspects to beginning the study of Indian music, it was not a total change of musical vocabulary for me. I had already been experimenting with many of the basic building blocks of Indian music, such as composing with modal melodies and using a drone and cyclic rhythmic patterns as a base to improvising.

From my first lessons with Ali Akbar Khan, it was clear that he represented an ancient tradition of music making that corresponded to what I was intuitively searching for. Training with a master of Indian classical music also reconciled my dual musical needs for spontaneous, improvised music making as well as study in a classical tradition. Ali Akbar Khan was the perfect example of a master of an age-old tradition, who was equally at home rendering traditional material as he was when dazzling audiences with his improvisations.

But why Indian music? There were other music traditions from around the world that were being introduced to western audiences during this time period. One might have a tendency to point to George Harrison, and conclude that Indian music’s great popularity was mostly due to the fact (or accident) that pop music’s most famous group decided to use the sitar in several of their hit recordings. However, George probably could not have just picked any of the world’s music traditions with the same effect. In fact, there are many reasons why Indian music is so well suited to global appreciation and study.

Indian music belongs to one of the oldest and richest living traditions of monophonic modal music, and as such, has had an influence on many important music traditions (including western art music), which have incorporated some of its basic musical concepts. Over the centuries, Indian music had been open to and subjected to, influences from other traditions, which has further widened its musical base and appeal. It has developed a wealth of instruments and styles, which have developed right up to the present day. Although Indian music is a so-called ‘classical’ tradition, with an ancient and highly developed theoretical base, it also has important links to the folk and popular styles, thus making it accessible to more than just an “elite” classical audience. The built-in possibility for creative input by performers through improvisation and composition, even within the constraints of the traditional structures, has kept Indian music in a continual state of renewal and readiness to adjust to changes in tastes and society. This has also helped it extend beyond narrow borders of social classes and geographic borders.

Although a form of music closely associated with India’s culture and even “spiritual life,” the actual performance of Indian music is not linked to any specific religious or liturgical functions. It flourishes in many contexts, from classical settings to pop music festivals, to intimate chamber music gatherings, and audiences do not need any special preparation to enjoy it.

All of the essential features of Indian classical music can be learned regardless of a student’s ethnic origin and it is relatively easy for a student of any culture to begin to study. In particular, the strong connection of all Indian music to its “vocal” origins makes it easy for any student to begin to learn without immediately tackling the technical challenge of the classical instruments. Of course, as in any serious musical discipline, a long-term study of Indian classical music requires talent, determination, and the right attitude toward the learning process.

Indian music has a wide range of expressive possibilities and forms and as such, has something for almost every listener. From the soft, meditative, almost prayer-like “alap,” to the intense rhythmic improvisations in the faster sections, – from ragas based on scales that are very similar to our own, to those which almost seem to come from another world, – from the subtle microtonal nuances of the most serious melodies to simple tunes taken from the rich folk music traditions – out of all the world’s monophonic music traditions, Indian music has perhaps the greatest variety of forms and range of expression.

II) A western performer of Indian music, both in and outside of India.

The very presence of non-Indian performers of Indian music attests to the global impact of this tradition. Even the small numbers of non-Indians who have reached high performance levels have sent an important message to the music communities, both in India and abroad.

In India, there have been a variety of responses to this phenomenon. First, it can be pointed out that connoisseurs of Indian music tend to listen with their ears open and their eyes closed, and do not place much importance on a performer’s ethnic background or place of origin. This fact itself tends to de-emphasize the issue of a non-Indian performer. Although initially curious at the appearance of a foreigner with an Indian instrument, the visual quickly gives way to the auditory, and the judgments are made mostly on musical content.

Knowledgeable Indian listeners are quick to praise (and criticize, for that matter), any musician, regardless of ethnic origin. Confronted with non-Indian performers of Indian music, their praise is also frequently accompanied by pride in their own culture. In this century, where it is more often the case that western culture is spreading throughout the world, Indians are deeply touched and proud that a non-Indian would value their music to such an extent as to make a serious effort to learn it. Their praise is not only reserved for advanced performers – even the efforts of a non-Indian beginner inspire pride and sincere encouragement for the student to continue the long work ahead. After one of my first performances in Calcutta, a senior stalwart musician approached me and said: “Very good performance! Keep up your good work – I’ll be interested to see you again after ten years!”

In contrast, some Indians have expressed a tinge of shame when confronted by a ‘foreigner’ who amply demonstrates a respect and mastery of their own musical tradition. This is even more prevalent among expatriate Indians, some of whom had never really listened to their own classical music. Of course, there are also a few who do not want to accept that anyone but an Indian can perform their music authentically. Sometime the comment can be heard “…oh, he plays very well – for a foreigner.” Even when praising a non-Indian musician’s performance, they will sometimes reveal a narrow and patronizing view: “You have that Indian feeling” – as if Indian feelings are somehow different and more authentic.

In the West, a non-Indian performer of Indian music faces a different set of responses. Sometimes these begin before any music is heard – even a non-Indian’s name is enough to make potential organizers reticent and some listeners suspicious. One common fear is that, if the performer is not an Indian, something must be missing. If this fear is not compensated by a sufficient understanding of how the music should actually sound, then it can be difficult to be receptive to a performance by a foreigner. On the other hand, some western listeners are completely open to the new experience of Indian music, and are not in least bit disturbed by the outward appearance of the performers.

I have experienced many of these responses during the last years but more recently, I have also noticed a greater openness on the part of promoters, audiences, and the academic community. To a large extent, this increasing acceptance in the West has been due to the positive feedback from my recitals in India – adding another dimension to the effects of global impact!

III) A music teacher integrating Indian music pedagogy with western music education.

The pedagogy of Indian music offers the western music educator a bridge to past musical epochs, when monophonic modal music, both composed and improvised, was an important part of the western art tradition. As these earlier periods of western music gave way to polyphonic, fully composed and orchestrated music, an important link to this past practice was lost, and with it the principles of pedagogy that were so essential in passing it on.

During the last twenty years of teaching at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis (the early music department of the Music Conservatory of Basel), I have researched and implemented the re-creation of a pedagogy for teaching medieval monophonic music. This research has drawn extensively on what I refer to as “the classroom of the east”, and I have integrated many aspects of the pedagogy of the east into the medieval music classroom. This has given western students both a fresh look at their own tradition as well as an introduction to the eastern source of these materials and techniques. It also serves as an excellent example of the impact of Indian music on the western music education. Here follows a brief excerpt from an article that deals with this subject.

Recent research has shown that improvisation played an important role in medieval music. The study of both theoretical treatises and the music sources indicates an extensive non-written, improvised tradition, existing alongside the composed, written repertoire. In particular, the 14th-century instrumental collections of ‘estampies’ and ‘istampitas’ give us a diverse and instructive glimpse into the medieval world of mode and improvisation. In showing a very consistent conception of modal composition and a diverse employment of improvised structures, they invite us to expand our understanding of the medieval art of melody making. In attempting to recreate the practice and pedagogy of medieval improvisation, it has been necessary to re-evaluate many of the basic conceptions that have become deeply ingrained in the world of Western classical music education and performance. This has not only involved a different look at the basic materials – i.e. notation, compositions, etc. – but also a look to other musical cultures. In particular, the strictly controlled practice of modal improvisation in North India has provided important clues as to how an extensive unwritten repertoire can evolve. (Basler Jahrbuch für Historische Musikpraxis, 1983)

In addition to working in the field of western medieval music, I have also been introducing Indian music to students for many years, both at the Music Conservatory of Basel as well as the Swiss extension of the Ali Akbar College of Music. Institutions like these and others around the world such as the Ali Akbar College of Music in the USA, the Rotterdam Conservatory, as well as a multitude of individual teachers, have clearly demonstrated that there is an extensive global interest, not only in listening to Indian music, but also in studying it. This promises to foster even greater global impact in the future, both by training aspiring performers, and by raising the level of sophistication of serious listeners.

IV) A composer exploring the contacts and contrasts between Indian and western music.

Indian music and the broader tradition of West Asian music to which it belongs, has had a significant impact on western music at various points in history. From the eastern origins of medieval chant, to the derivation of the lute from the oud, to the contact and rich exchange between musicians in the international climate in the royal courts of medieval Spain, East and West have met frequently during many periods of music history. More recently, during the last century an increasing number of western composers and performers have been inspired by various elements of Indian music.

Whether purely fascinated by the exotic sounds of the instruments, or inspired by the concepts of the Indian rhythmic cycles or the variety of the raga modes, western composers, both in the classical and popular genres have been increasingly integrating Indian music into their works. Sometimes the elements are hidden, subtly integrated into modern compositions. Sometimes they are audible to all, such as the characteristic sound of the sitar heard in the Beatles’ Norwegian Wood. In other instances, composer/ performers have utilized a variety of elements – extended time cycles, exotic Indian scales, as well as Indian instruments – as in the music of Frank Zappa. The frequent appearance of tabla on soundtracks from recent movies and on television confirms that Indian music has become woven into the fabric of western contemporary music.

Performing musicians have also been a great stimulus to musical contact and influence. Through travels, migration, and even concert tours, performers tend to be curious about regional traditions, and often times are ready to experiment with local artists. As travel increasingly makes the world a smaller place, the frequency of contact and the resulting “crossover projects,” “fusion” bands, and new “world sounds” have flooded the record stores, at the same time creating the genre known as “world music.” Although it appears that many of these international get-togethers are short lived, they do inspire contact, openness, and inspiration.

Indian music has played a significant role in this phenomenon and I have taken part in a number of experimental encounters, both as a composer and performer. Some of these projects have been east-west encounters, as with several performances including Indian and medieval music. Others have been east-east experiments: for example, a meeting of Indian and Persian music and a meeting of Indian and Turkish music. Others still have attempted to house a number of traditions under one roof: in a recent composition which I titled Modal Tapestry, Indian, classical western, modern, jazz and popular musicians were assembled to perform compositions and improvisations in a variety of different musical styles.

For general audiences, these projects can be very popular. Not only do they bring together musicians in a spirit of discovery and exchange, but they also expose audiences to musical styles that they would not normally encounter. In a concert mixing elements of medieval music and Indian music, there are also two distinctly different types of listeners. The Indian music enthusiasts in the audience might not go to a concert of medieval music and the medieval listeners might not go to a performance of Indian music. This kind of musical experimentation offers a venue where new impressions are available to many who might otherwise not be exposed to them.

Conclusion

There is no doubt that in recent years, Indian music has had a tremendous global impact. But there are many questions about the future of Indian music’s place in the world. Will it continue to spread, develop, and deepen, both in India and abroad? In the parts of the world where it has had the greatest impact, will there continue to be an even greater appreciation and understanding? Will the non-Indian performers and schools in the USA and Europe continue to thrive?

In India, will there be an effort to reverse a trend that could be described as globalization in the common meaning of that term? Or will the continuing invasion of western music increasingly divert the Indian youth to the MTV music culture? Will today’s classical performers remain faithful to the rigors of the ancient tradition, or will they be drawn into the “world music fusion” movement, searching for whatever stylistic combinations will sell recordings in the short term, without concern for what will happen to their traditional riches?

Although these questions cannot be answered with any certainty now, it is at least reassuring to keep in mind that classical Indian music has survived and thrived for many centuries, during which time it has shown both resilience and readiness to develop. In fact, there is ample room for optimism that the growing global interest for this highly evolved art tradition will inspire serious students of Indian music all over the world to continue exploring the rich tradition of ragas and talas.

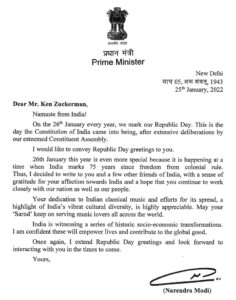

Ken Zuckerman, March 2002