Perspectives of a student, performer and teacher

Table of Contents

Introduction

A Student and Performer of Western Music discovers Indian Music

Serious Study – A Disciple sets out the Long Path of Learning

Obstacles along the Way

Physical Obstacles

Lack of Repertoire

Listening Experience

Cultural Context

Social Pressures

Advantages of a Western Music Background?

Advantages of being in the West?

A “Western” Performer of “Indian” Music

A Teacher of Indian Music in Europe

A Teacher of Western Music in Search of the Teaching Models

Conclusion

“It is not a question of Indian music, or American music, like that; any type of music, in tune and in rhythm, gives you food for your mind, heart and soul“. Ustad Ali Akbar Khan

It often appears that we live in a world of dualities. We tend to interpret our impressions in terms of black and white, good and bad – even east and west. Although in some situations this may be convenient, it tends to keeps us from seeing the more subtle relations that unite our world. The theme of Indian music and the West immediately suggests several dualities: geographical, cultural and musical. And it is exactly in this context that Maestro Khan’s simple and straightforward statement is an important reminder. It is a wonderful example of his musical vision and is an invitation for us to stay aware of the universal elements of music, even as we concentrate on the diversity and contrasts of its specific forms. I believe that if we keep his statement in mind, it will help us come to a fuller understanding of the complex and fascinating theme before us.

In addition to exploring the above ideas, this paper traces several of the important stages of my musical development during the last thirty-five years of studying both western music and (for the past twenty-four years), Indian music. I have tried to recount how my impressions during some of these stages helped me to better understand my roles as a student, performer and teacher . The most important points I wish to make may be viewed from the following perspectives.

From the perspective of a beginner, curious to enter the world of Indian music

There is nothing intrinsically “foreign” or “exclusive” about Indian music which makes it inaccessible to anyone who is attracted to it, and who has a wish to begin to learn.

From the perspective of a serious student, engaging in a long-term study

All of the essential features of Indian classical music can be passed on from the guru to the disciple wherever they happen to be living and regardless of the student’s ethnic origin. Depending on talent, determination, and attitude, it is possible for a student to overcome whatever obstacles may be waiting, and reach the highest level of understanding and execution.

From the perspective of a western performer of Indian music

The most discerning connoisseurs of Indian music tend to listen with their ears open and their eyes shut, and do not place much importance on a performer’s ethnic background or country of origin.

From the perspective of a teacher, working in a variety of western music contexts

Indian music can be introduced effectively in the West at many levels, from primary school through the professional music conservatory. Also, Indian music pedagogy has much to offer the western music educator.

A student and performer of western music discovers indian music

I grew up in the midst of a great cultural curiosity in everything from the “east”. I must admit however, that I was not actively involved in the movement and I barely noticed some of the momentous “Indian” events of the late 1960’s – George Harrison with his sitar, Ravi Shankar at the Monterey Pop Festival, etc. But as a music student in my own culture, I was gaining experience in a number of western musical styles. There were elements in many kinds of music that I found attractive – from folk music to rock’n’roll, to jazz and classical. I was also very interested in composing and improvising. But somehow I was not completely satisfied by any one style and was searching for my proper place as a musician. It was at this moment that I had the good fortune to see Ustad Ali Akbar Khan perform at the university where I was studying.

I do not recall this encounter as being so much of a cultural confrontation with something “foreign” or exotic. It was rather, a purely musical discovery. I was astounded to hear a musician show such technical excellence, evocative feelings and imagination, on an instrument that seemed to have no limitations for expression. It was somehow like a music that I had imagined, but neither had the ability to execute, nor even a form in which to develop it. I was very soon aware that Indian music represented a richer world of melody and rhythm than I had ever come across before. I sensed that the maestro was improvising, constantly searching for new combinations, as I was also searching rather naively in my attempts on the guitar. But I also had a feeling that the music was coming from somewhere deep, not only from within the performer himself, but also from a depth like the roots of an immense tree. I learned only later that I was intuitively perceiving the roots of an ancient tradition. But although it was a new and thrilling experience, it never seemed essentially foreign or exotic – on the contrary, it was strangely familiar.

There were musical reasons that helped explain the familiarity that I felt upon first hearing Indian music. Throughout my early musical training I could not find one musical style that satisfied all my interests. Although I enjoyed the melodies and story telling of western folk music, my urge to compose was stifled by the limitations of the genre. Also, while I felt at home with the rhythmic power and spontaneity of rock-n-roll and blues, both styles lacked a certain refinement and depth of expression. Even the enjoyment and admiration of the improvisational skills of jazz musicians was sometimes offset by a lack of feeling and lyricism in their music. And my respect for the great masters of western classical music was also tempered by the realization that although it encompassed a wealth of impressive music, it did not fit my means of expression. First of all, there did not seem to be any place for a young composer who wanted to work in the classical styles. There seemed to be a rule that a modern composer could never hope to approach the skill of the old masters (Bach, Beethoven, Brahms), so why bother? Instead, a modern composer must create something “new” and “different”, and I was not interested in most of the new and different trends in contemporary music. In addition, there was a general belief that composers should compose music, not perform it and vice versa, performers should interpret music and not try to write it. Finally, it was generally forbidden for a classical musician to improvise with the composition during a performance. This was all a bit frustrating to a young student who wanted to be involved in all aspects of making music – from composing, to performing, to improvising.

Indian music, on the other hand, seemed to satisfy all the needs: melodic refinement, rhythmic subtlety and power, traditional roots, centuries of classical evolution, and yet a music that was newly composed and improvised during each performance. I was ecstatic! I had been on a musical odyssey since childhood, searching my American roots and European heritage, and found myself at home in a style I never would have imagined!

Serious study – a disciple sets out on the long path of learning

I began studying Indian music full of idealism to enter a new musical world. I had no ambition to become a professional Indian musician nor did I have an idea how long the training would last. Although I was already twenty years old at the time, my attitude towards learning was more that of a child than of a young adult considering a possible profession. In retrospect, this was a blessing in disguise. Had I known from the beginning that it would take so many years to become proficient, I might never have begun.

A child-like approach is exactly what was necessary to enter the world of Indian music. In fact, Ali Akbar Khan (referred to as Khansahib for the remainder of this paper), continually had to remind us to let go of our “western” analytical, intellectual attitudes towards learning, in favor of a more subtle state of listening and openness. Particularly during those moments when we felt overwhelmed by the complexity and depth of the subject, he would remind us to relax, stop asking questions, and just listen. In this way, he helped us overcome our tendency to over-intellectualize, which is one of the biggest obstacles facing a western student of Indian music.

I believe that Khansahib made several adjustments to his teaching methods in America. For example, most of the teaching has taken place in the context of a classroom, sometimes with many students trying to learn at the same time. This was necessary for several reasons. First, there were so many students who wanted to learn that he could not possibly work with them all individually. Second, he did not wish to exclude anyone. He realized that it would be difficult to pick out the few gifted and determined students who would be able to endure a rigorous training for many years. Third, the thousands of students who received basic introductory training under him provided the foundation for an educated audience, which was also needed to help the music flourish in America. Finally, he realized that because the entire subject was new for his American students, they would need some time to catch up until they were ready for individual training.

Obstacles along the way

There were several obstacles that immediately faced Ali Akbar Khan’s western students, and he helped us address them in different ways. They included:

Physical obstacles – Some of Khansahib’s students had never touched an instrument before, let alone a sarod or sitar. Therefore, physical mastery of the instrument would take longer and could not be a prerequisite for study. Khansahib was infinitely patient as he helped us compensate for beginning rather late in life. In addition to coaching us through all the necessary technical exercises, he also simplified the initial series of compositions. This enabled us to learn and enjoy the music right from the start, in spite of our limited technical abilities.

Lack of Repertoire – Many of Khansahib’s students did not even have much experience listening to classical Indian music before beginning to study. Therefore, it was a daunting task for Khansahib to introduce us to the huge repertoire of vocal and instrumental compositions in the main ragas. But he was able to do this quite efficiently in the classroom context. A few students gradually became adept at learning and notating the compositions quickly, thus allowing him to give a large quantity of material in one sitting. A standard system of notation was also developed and this gave beginning students a way to work on the compositions at their own pace. During the course of many years, this method enabled students to acquire a large repertoire of traditional compositions in all the important ragas and talas.

The process of learning hundreds of compositions directly from Khansahib was also an important training. We were constantly demanded to sharpen our listening skills to hear all the melodic and rhythmic subtleties of Khansahib’s style, both in the vocal and instrumental classes. He exhorted us to pick up his musical phrases immediately, in the same way that he learned from his father. Visiting students from India are often impressed at how quickly Khansahib’s disciples learn in this way, and are relieved to be able to take the notations and class recordings home with them to slowly decipher the music.

Now after thirty years of lessons, the volumes of notated music have grown into a vast collection of compositions that students will be able to profit from for years to come. In addition, almost every class at the Ali Akbar College has been recorded. Thus, the unique combination of audio and written materials will provide future generations with one of the most extensive collections of a musician’s teaching ever documented.

The years of classroom experience has also been an excellent preparation for individual lessons. Khansahib continues to sit regularly with his most advanced students in a quieter setting, with no more than two or three at a time. Here he is able to teach all the subtleties of the music, and evaluate each student’s progress. During these sessions he demands an even greater level of attention and has no hesitation to scold us for not exactly reproducing his musical phrases. Those who have not had the preparatory time in the general classroom usually end up becoming frustrated for not being able to learn quickly enough in this setting.

Listening experience – Most students in the West have grown up listening to many different styles of music – but not necessarily classical Indian music. The teachers at the Ali Akbar College always encouraged us to listen to a wide variety of Indian vocal and instrumental styles to compensate for this. Also, due largely to Khansahib’s efforts, the San Francisco Bay area has now become one of the major centers for Indian music performance outside India. A steady flow of musicians has insured that we have a broad exposure to many fine musicians from various styles.

Cultural Context – The question is often brought up, how can one really uproot an art form from its cultural context and plant it somewhere else? Are there elements of the art that suffer when moved into another culture? In this respect, Indian classical music is not so different from various forms of “western art music”. For example, it is usually performed in the relatively neutral context of performance halls, rather than as part of specific social or religious rituals. In this way, it “travels” easily and today is one of the most popular forms of classical music listened to around the world.

However, the teaching of Indian music cannot be simply reduced to learning notes and rhythms. In this respect, Khansahib has done an impressive job in transmitting not only the music elements, but much more. For example, his extensive knowledge of all the vocal forms (dhrupad, khayal, thumri, etc.), has not only given us a wide variety of repertoire, but also an introduction to Indian languages, poetic forms, religions and philosophy. He also regularly enhances the music teaching with anecdotes from his upbringing and his many experiences as a performing musician in India. These have provided us with a better understanding of the roles of music and musicians in Indian society.

Khansahib has also helped us understand and respect the special relationship of guru and disciple, and has allowed it to deepen in those students who have been with him for many years. Without demanding a superficial observance of rituals or behavior, he has let the essence of this important relationship grow naturally.

In short, one could almost say that when Ustad Ali Akbar Khan came to America, he actually brought a piece of India with him. In so doing, he demonstrated that the essential features of the tradition can be passed on from guru to disciple, even in a very different setting than the original culture provides.

I was very satisfied to study with Khansahib in the western context, but at one point I also began to feel a need to see the place where the music originated. This coincided with a deepening interest, not only in the music, but also in the philosophy and cultural life of India. My initial impressions of India were both very positive and shocking – and yet somehow familiar. The warmth of the people, their enthusiasm in life, detachment from the chaos, sincerity, spontaneity – their entire outlook began triggering a whole series of responses within myself that have taken years for me to understand and assimilate. I received an overall impression that although India is an ancient land and its people steeped in profound traditions, anything can happen in the moment. This was in fact, so similar to what I felt from the music that it made a deep and lasting impression on me. It also gave me an even richer appreciation for Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, and how he managed to bring so much of the “Indian essence” to us through the music.

Social Pressures – An additional handicap that many of us faced during the years of study had to do with pressures from our own society. On the practical side, it was extremely difficult for many to finance a long-term study of Indian music, especially without any prospects of gainful employment upon completion. This forced many to take part-time jobs, which also cut into the available time to practice. Of course, these problems also exist in India but at least there is a tendency for children there to begin their basic training while still under the care of the family. In general, western students have begun their study approximately ten years too late, and it is a real struggle to catch up.

Another more subtle pressure is faced by students in America. This has to do with the fact that although there is a growing appreciation for Indian music in the West, there are very few possibilities for a musician to earn a living from it. This creates a kind of stigma that is difficult to overcome, both economically and socially. Often times, to be a non-Indian performer of Indian music means to be either ignored or even ridiculed. Of course, this fact cannot not deter a dedicated student from learning. But at some point he or she must find a proper place within society. Mostly this means earning a living in a different field and trying to maintain the music as a serious hobby.

In general, although western students face many obstacles, none of them can be considered insurmountable if a strong wish to learn is combined with talent and dedication. In any pursuit, each of us brings our own strengths and handicaps. The real task, whether one is Indian or from the West, is to face one’s weaknesses squarely and proceed steadily and mercilessly to overcome them.

Advantages of a western music background? Although many of us began studying with a number of handicaps, as discussed, we also had some potential advantages. Those of us who had studied western music before had already acquired many important musical techniques, and even some skills which are more difficult to learn in India. For example, in the West, the ability to play in an ensemble is extremely important and is given much attention during a student’s training. It is also important in Indian music, especially in the interaction between the soloist and accompanist, but it is not specifically taught most of the time – performers are expected to develop it naturally. As a result, some master it themselves and others never seem to give their attention to this important aspect. This can occur with both soloists and accompanists, and it is a pity that the lack of communication can sometimes spoil the overall performance.

Also, because most performances of western classical music are restricted to the interpretation of a fixed composition rather than improvisation, much attention is given to musical details like phrasing, articulation and tonal quality. These are also important in Indian music but often times are not directly taught: the student is expected to develop these skills with very little guidance from the teacher. As a result, it sometimes occurs that the performance of an otherwise accomplished Indian musician is marred by an unpleasant tonal quality, careless phrasing, or insensitivity towards dynamic modulation.

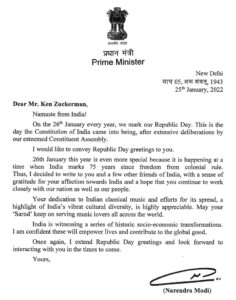

Advantages of being in the West? It is generally agreed that the single most important factor in taking up a serious study of classical Indian music is the guru. Without the right teacher, even the most talented student will not be able to evolve into a great musician. In this respect, we had the good fortune to be in the “right place at the right time”. Even as we began to work with Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, many of us were not fully aware that we were studying with one of India’s most renowned artists. Not only is Khansahib recognized as the greatest living sarod maestro, but he is also a consummate composer, a vast storehouse of traditional knowledge, and a patient and generous teacher. Being under the guidance of such a master – wherever he is living, is perhaps the most important advantage that any Indian or western student could ask for.

A “western” performer of “indian” music

Although I had begun to give a few small performances in the West, it was only after visiting India several times and playing for audiences there that I began to imagine that one day I would be able to be a performer of Indian music. I felt a warm and genuine response from the Indian listeners. It seemed that they were not only appreciating my efforts as a westerner, but also the music as being a faithful rendering of Ali Akbar Khansahib’s style.

I also felt that there was an appreciation of my basic musical instincts, independent of the sarod, or the forms of raga and tala. This was an important confirmation of what I had always felt – that a musician’s feelings can be expressed through different forms. Although at that moment the vehicle for expression was the sarod, using the classical Indian forms, they were actually the same basic feelings that I had been trying to express through music since the age of ten, while playing western music on the guitar. It was indeed, an important confirmation to see that an Indian audience was also able to go beyond the outer forms and get the essence of my music. It is also interesting that sometimes they would proudly proclaim that what I really had was “Indian feeling”. But this is understandable and in a larger sense, also brings us back full circle to Khansahib’s statement; “…any music, in tune, and in rhythm, gives you food for your mind, heart and soul.”

Although each subsequent visit to India brought even more encouragement from listeners, fellow musicians and music critics, the response “at home” was often times frustrating. It seemed that a certain part of the western listening audience had difficulty accepting that Indian music could be performed “authentically” by a non-Indian. And it was clear that this judgment was not based on any knowledge of the genre but rather, was a simple case of prejudice. If the name and ethnic background did not fit, there must be something flawed in the presentation. Although this situation has improved somewhat over the years, it is still there, and comes up mostly in the West. But viewed historically, the performance of Indian music by westerners is still a new phenomenon, and some people may need more time to adjust. In fact it was not many years ago that some of the first Japanese virtuosos of western classical music began demonstrating their skills in America and Europe. The initial responses were not entirely enthusiastic, often because the picture of an oriental-looking violinist did not fit the normal expectations. But today, very few people think twice about this issue and some of the finest performing virtuosos are from far eastern countries. I am convinced that with time, if westerners are able to continue maturing as performers, then even the strongest skeptics will also become more open as listeners.

A teacher of indian music in europe

During the past fifteen years of living in Switzerland, I have taught Indian music in a number of different settings. These have included demonstrations and workshops for primary school children, introductory classes for adults, courses aimed at music students at the Conservatory of Music, and long-term training at the Ali Akbar College of Music in Basel. In every situation I have been impressed at how well students of all ages and levels respond to Indian music.

For example, children react spontaneously to the excitement of the rhythms and are eager to learn the Indian solfege syllables. I always engage them actively, with reciting, clapping and singing. For them, it is a kind of game and they easily take in the basics of the music. Sometimes years later, the children who I worked with in this way still remember the experience.

I also regularly introduce Indian music to adults, and am consistently impressed at the variety of people who are drawn to the aesthetic experience that Indian music brings. In general, these students are more interested in a general introduction rather than becoming accomplished singers or players. Although they are full of enthusiasm to learn, adults are much slower than children in picking up the basic skills of Indian music. In the same way that I was admonished for my “western”, analytical approach, I am often in the position reminding students to relax, listen, and try to resist the urge to take in the music primarily with the mind.

Those students who take part in the introductory courses in Indian classical music also provide the foundation of an educated audience. Visiting musicians have often commented on quality of the listeners in Basel. They enjoy seeing the students in the audience quietly keeping the tala during a performance, and also appreciate the extra response that comes when listeners are already familiar with the basic ragas.

Surprisingly, sometimes the most difficult ones to reach are the music students at the Conservatory. They tend to be absorbed in their own studies and suspicious of other forms of music. But some are curious to try out something different from their normal music curriculum. A few even go on to studying the Indian instruments for a time. When I think back to my own accidental introduction to Indian music, I am inspired to give a chance to as many students as possible to discover something new.

A teacher of western music in search of teaching models

At one point in my music studies I became fascinated with the relationships between Indian and western music. Particularly in the area of western music of the Middle Ages, I observed many similarities in terms of modes, melodic styles, rhythmic construction and ornamentation. Although there are very few written documents from this early period of western music, it became clear that there were a number of interesting similarities, especially in the repertoire of medieval monophonic songs and instrumental dances. These forms also exhibit strong evidence of a non-written, improvised tradition of music-making existing alongside the written repertoire.

This evidence has led to extensive research to reconstruct a performance practice for medieval music, and a methodology for teaching. At one point I also began to experiment with using elements from Indian music pedagogy in the western medieval classroom. Although there is insufficient space here to go into details, the results so far have been very encouraging, and the research is continuing. I have also utilized Indian teaching techniques in the ear training classes of the Music Conservatory of Basel, with very positive results.

Conclusion

Indian music has found a home in the West. It is a home where an audience of educated listeners can enjoy the finest performers of the art, a home where students of all levels are learning, and a home where a small number of dedicated performers are maturing. It is a new home and only time will tell whether the solid foundations that Ustad Ali Akbar Khan and other pioneers have laid, will continue to evolve into lasting structures. But it is truly remarkable how much has been built in such a short time. It is also living proof of the universal appeal of classical Indian music.

Ken Zuckerman, September 1996

Ali Akbar College of Music – Switzerland

Music Academy of Basel