A JOD OF TWO CULTURES

Indian Express – Weekend Edition

Bombay – Saturday, August 8, 1992

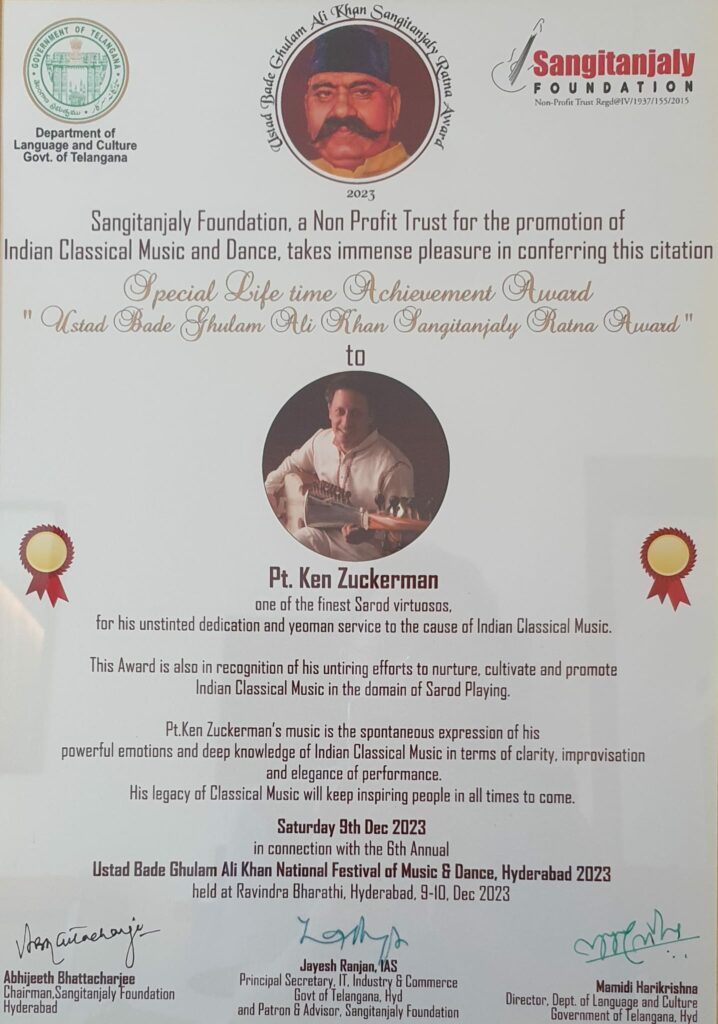

Ustad Ali Akbar Khan rates him as one of his most gifted disciples, while connoisseurs recognise in Ken Zuckerman’s felicity with the sarod the soul of his guru’s artistry. Sumit Savur in conversation with the internationally acclaimed Jewish-American sarodist, who has astounded audiences here and abroad with his mastery over the alien instrument. Ken Zuckerman was born to Russian-Jewish parents in America. In 1971 he was swept off his feet by a chance encounter with sarod maestro Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, and has been his ardent disciple since. He directs the Ali Akbar College of Music in Switzerland, while also teaching music at the Music Academy, Basel.

Ken, how do you account for your interest in the sarod?.

It was not so much the sarod, as my fascination with Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, which eventually led me to California to try out a summer studying Indian music. In fact, I began my studies with the sitar. I switched to the sarod later.

Did you already possess a Western classical background?.

I knew classical music, but I was not a practitioner. It was a long-term background, not particularly classically focussed. I was more in to the lighter forms; played the electric guitar, rock’n’roll, the acoustic guitar, did a lot of composing in jazz and folk music. Indian music has such a broad spectrum of expression through its raag vistaar, bols, layakari…

Did you have any communication difficulties?.

Well, the Ustad always spoke to us in English and his accent was a bit difficult initially. He taught us step by step. That made the task of learning less daunting. The main accent was placed on singing. Khansahib led the class in singing and we were encouraged to follow first in singing as closely as we could and later repeat the tune on the same lines with our instruments.

The methodology of teaching was very direct; the terminology came as we went along. As most Indian music is taught by the ear, a general difficulty for most Western students is to give up the eye contact with the music sheet and cultivate the capacity to listen, commit to memory and develop the mental capacity to reproduce music from recollected lessons. It is an education in itself.

You certainly have assimilated our music very well. How many hours of riyaaz have you put in to attain your level of proficiency?.

Over the years, it has been more intense. Having begun to learn as a young adult, I had to earn a living and as such I had to deny myself the opportunity to exclusively practise on the sarod. Next to my studies, I was always doing something: washing dishes, selling shoes or giving guitar lessons, so my riyaaz was always limited. In these 20 years I have put in the riyaaz of listening to my Khansaab and absorbing all I can. I know I have tried all I can to capture the essence of his style, though I still need to make myself technically more proficient in terms of tayyari.

Tayyari now seems to be the watchword. There is a marked tendency to show off possibilities with the instrument rather than the raga. You, however, seem to favour a quieter melodic line and almost studiously avoid the jazzy crescendo in the progression of the raga..

I have a tendency to go for the lyrical approach and as such my riyaaz has been slanted more on the alap and slow development of the vistaar. The mood of a raga is the essence in Indian music. This is what my Ustad taught us and demonstrated through his playing. If the fundamental melodic line if the raga is sketchy, mere tayyari or striving for speed will not give the desired effect. When I began coming to India, some of these young sarod players in Calcutta would laugh at me because I wasn’t playing very fast. Having learnt outside India, I am lucky I have been out of this vicious circle.

You’ve had the honour of performing alongside your guru.What were your feelings on such occasions? And how do fellow Westerners react to your performing an Indian instrument? .

I view such opportunities as my guru’s blessings and regard performing with him an extension of my learning process to a higher plane, to the performing stage. I consider it a deep honour to be taken with him to the concert level.

Westerners who understand Indian music can see that I have learnt it the proper way. Those who hear me with reservation are those who think Indian music is something sacred, and to be pure must be performed by an Indian. This close-minded attitude exists in America and Europe where these people are also concert promoters. That’s why friends like Zakir Hussain advised me that if I wanted to be accepted in Europe and America, I must prove myself authentic in India.

You seem to have convinced audiences here of your authenticity. Hasn’t this changed the response back home?.

Until five-six years ago, I was up against a brick wall back home despite studying for 15 years and receiving good notices here. Then, Khansaab began to take me with him on the stage in America and Europe. My friends Zakir Hussain and Swapan Chowdhary also agreed to play with me on the concert circuit, and these things did the trick. Impresarios were then convinced that if Khansahib, Zakir or Swapan were performing with me, I must have some standing. It has been an uphill struggle, but I am not in a hurry.

Your Ustad also pioneered a few original compositions like Chandranandan and Gaurimanjari. Are you acquainted with them?.

I play Chandranandan myself. It is one of my favourite ragas. It is his very own special raga – an artistic achievement – Kunst Werk as we say in German. Gauri manjari is way out. I am still years away from performing it as it combines so many elements; has all of 11 notes.

Now that you have established yourself, what next? An international jugalbandi in the manner of your guru?.

The jugalbandi of Khansahib with Raviji was an extraordinary musical phenomenon. Both had been brought up in the strict discipline of Baba Allauddin Khan and probably trained to perform together. There has been none other like it since. As for me, I did try it recently with a fellow American sitarist, James Pomerantz, a long-time disciple of Khansahib, at the Ramkrishna Mission, Calcutta. While I am quite open to it, a jugalbandi is something on the fringes. The main pursuit in this music is the dialogue between the instrumentalist and the tabla-player, which interests me more.

Do you employ the same techniques as your guru while teaching?

The basic approach remains the same with those who wish to learn music. Some students, however, only come for an introduction – they do not aspire becoming performers. They are taught in a slightly different way. Besides teaching them compositions Khansaub taught me, we listen to music paying attention to different aspects of the raga. For those who evince deeper interest, I recommend a summer course with Khansahib at California. I also conduct lec-demonstrations in public schools in Switzerland, mainly to help students develop an ear for it. Those listening regularly can now keep tala during a recital.

Has this appreciation led to any student taking to the sarod?.

Those who come already have their professional goals fixed. They might be fascinated with the sarod, but few are foolhardy enough like me to give up everything else and go for it without any assurance about the future. (Laughs)

Apart from our music, what other aspects of the Indian way of life have you imbibed?.

I appreciate the average Indian’s outlook on life. The mentality is so different: patient, philosophical, accommodative and full of tolerance. One thing which attracted me to Khansahib was the way he is, the way he speaks, his outlook on life; it’s all in harmony. Music seems the natural expression of his philosophy. Music encourages one to go into the world of vibrations where it doesn’t matter whether you are saying a Hindu chant or a Moslem prayer. It is a stage beyond that: a spiritual experience.

I couldn’t help feeling as I left that this gentle American was a fitting cultural emissary to conquer the world with his music. While indigenous maestros captivate foreign audiences abroad, this kurta-pyjama clad alien is here to bring home the innate sweetness of the sarod with his utterly disarming ‘Indianness’….